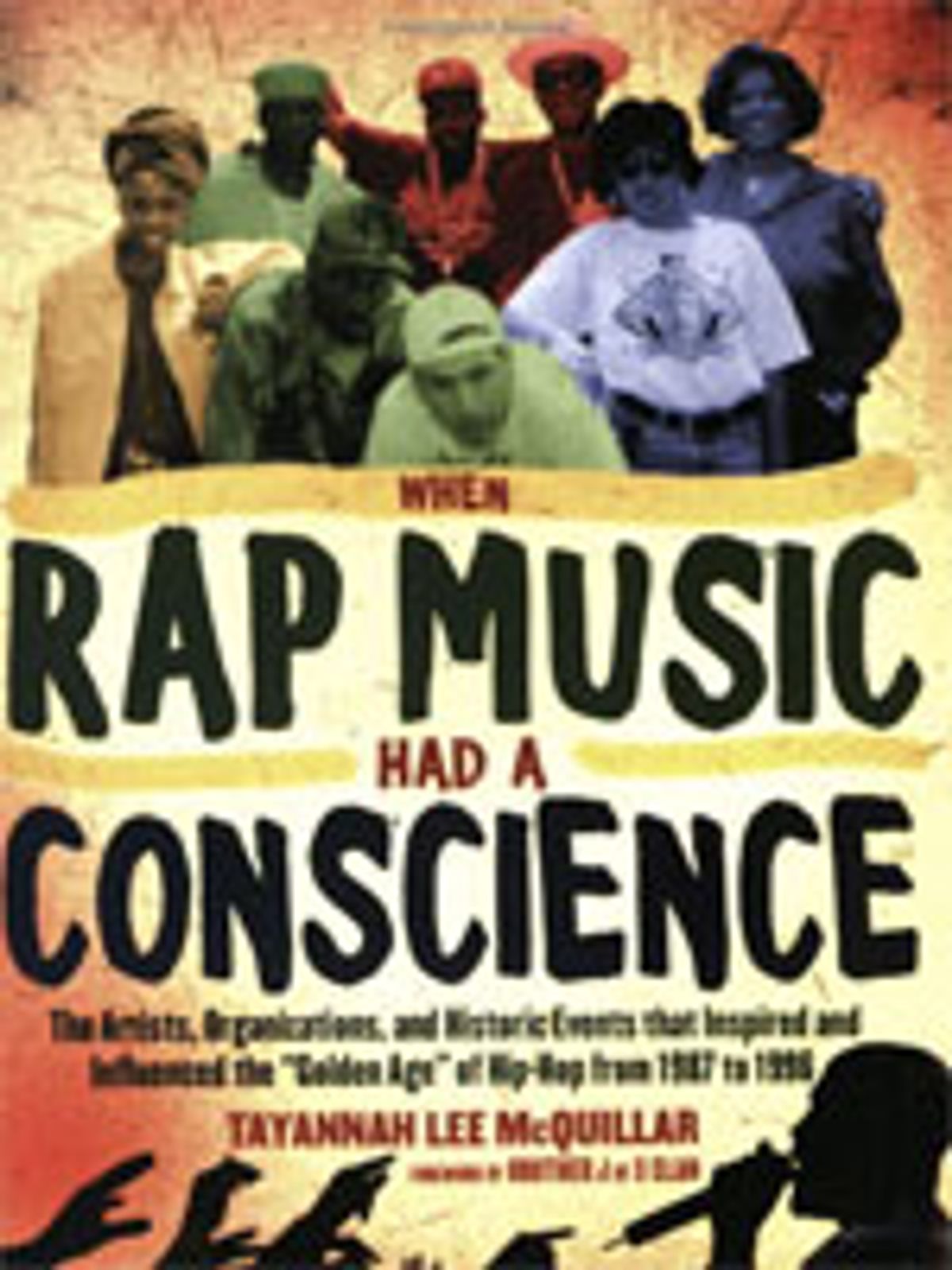

What comes to mind when you think about rap music? If you've been paying any attention to the high-profile rap releases of the last decade, it wouldn't be surprising if that question compelled thoughts of violent lyrics, booty-filled videos and images of decadence and materialism. But as Tayannah Lee McQuillar points out in her book "When Rap Music Had a Conscience," in stores on April 10, it wasn't always that way. McQuillar's book is a celebration of the "Golden Age" of hip-hop (defined therein as occurring between 1987 and 1996), when artists like Public Enemy, De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest were able to carve out a space for themselves with their thoughtful, political music. The book isn't just a look back, though; it's also a lament over the current state of rap music, which the author views as tipping too heavily in the direction of the "gangster" and "crass materialism" and away from the progressive values of the golden-era rap she holds dear. McQuillar took time out from her teaching job in New York to speak to Salon about the new book.

What comes to mind when you think about rap music? If you've been paying any attention to the high-profile rap releases of the last decade, it wouldn't be surprising if that question compelled thoughts of violent lyrics, booty-filled videos and images of decadence and materialism. But as Tayannah Lee McQuillar points out in her book "When Rap Music Had a Conscience," in stores on April 10, it wasn't always that way. McQuillar's book is a celebration of the "Golden Age" of hip-hop (defined therein as occurring between 1987 and 1996), when artists like Public Enemy, De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest were able to carve out a space for themselves with their thoughtful, political music. The book isn't just a look back, though; it's also a lament over the current state of rap music, which the author views as tipping too heavily in the direction of the "gangster" and "crass materialism" and away from the progressive values of the golden-era rap she holds dear. McQuillar took time out from her teaching job in New York to speak to Salon about the new book.

The majority of any popular medium tends to be of low quality and morally questionable. Why is it particularly problematic for mainstream rap to be that way?

Because it leads to a criminal mentality in the youth. I teach in an alternative high school and see the effects of this music every day. As adults we can watch gangster films -- "The Sopranos," any violent material -- and acknowledge that it's a fantasy, but I think that people forget that children are children and they take this stuff to heart. I have students come in every day -- it could be someone who's very bright -- but they have to pretend to be a thug. It's sad. A lot of kids think that keeping it real or proving their manhood means a rite of passage where they're either exploiting their own community by selling drugs or exploiting the women in their community -- all the stereotypes you see in hip-hop today are what these kids are trying to live out.

But how closely can we draw causal links between rap music and criminal behavior?

There are definitely other circumstances. I want to be clear that I'm not saying that rap music causes any of these behaviors -- this is something that's in the culture. Art is a reflection of the culture at large. If there's misogyny or sexism in society, it will be reflected in the music. The problem is not that rap music causes these behaviors but that there's no balance anymore. I'm not that old, but when I was growing up we had rappers that were talking about the same exact things that people are talking about now -- girls, cars, killing your enemies -- but we also had artists talking about other things and they were played on the radio too. That situation doesn't exist anymore. So no, I'm not blaming rap music, I'm just calling for a balance like there was in the late '80s and early '90s.

It's hard to know how your message resonates beyond the black community, and given that white listeners make up a large portion of the market for gangsta rap, what has to happen for record companies to be motivated to stop pushing that style of rap?

The thing is, black people have always set the trends in the United States. We're the epitome of cool -- it's always been that way. So if black people don't see gangsta rap as cool anymore, if they see it as played out, then even the white kids won't be interested. Right now, the point is that gangsta rap is cool, it's masculine, it's hip. Where that will change is when black kids say, "Hey, you listen to that? That's over." That's when white kids will stop buying it too.

-- David Marchese

Shares