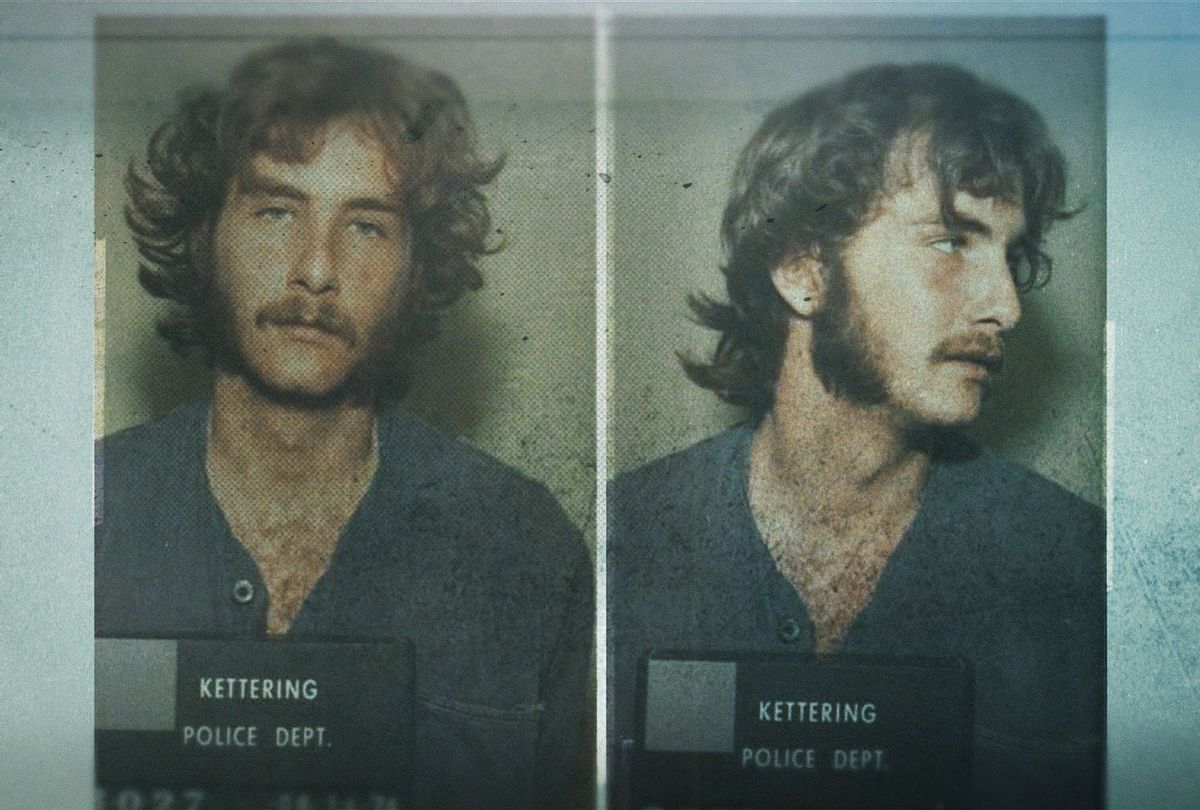

In "Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan," Netflix's latest, shocking true crime project takes audiences on a sordid and haunted journey through the life and alleged crimes of Billy Milligan. The man was famously accused of kidnapping and raping three women at the Ohio State University in the 1970s, only to be acquitted by citing and blaming the crime, which he confessed to, on his dissociative identity disorder.

Decades later, myriad questions and contrasting perspectives remain about Milligan, his crimes, and his mental condition. After being acquitted, Milligan spent time at varying mental institutions, where psychiatrists analyzed and debated his condition for years. But as more and more media attention became attached to his case, and the continued sprees of crime and violence connected to his name, Milligan soon emerged as a star — dating women, having a wedding at a mental facility, living it up in Hollywood.

But as authors wrote sympathetic or at least humanizing books about Milligan, his alleged victims – including three young women and very possibly several male murder victims – vanished from the narrative. The same documentary that interviews Milligan's sister about his being a doting uncle to her kids and a good friend of Milligan's who actively aided him in escaping confinement, also speaks to s a law enforcement agent who expresses disgust with all of this. "No one cared about his victims," he observed, noting how instead, the culture obsessed with and fixated on Milligan's mental condition.

"Monsters Inside" presents a compelling yet concerning story, as audiences may consider the ethical questions it raises about how media portrays mental illness, or the entertainment industry's enduring obsession with serial killers and violent men like Ted Bundy. Such storytelling can often elevate violent men to celebrity-like figures, at the expense of their victims and other sexual assault victims, who are relegated to footnotes.

These issues are among the many discussed behind the scenes in creating "Monsters Inside," French director Olivier Megaton, who's directed "Colombiana" and two of the "Taken" films, told Salon.

"For the entire documentary, we couldn't just be against him, because you need to have not necessarily empathy, but you need to like the subject a little more to go inside, and show him, and understand what happened in his life," Megaton said, of the creative decision to humanize Milligan despite his alleged crimes.

In the interview below, Megaton also discusses the cultural context of the crimes, the contrasts in American and European reactions to Milligan's stories, and the common controversies that true crime and psychological stories like Milligan's are often steeped in.

The intro sequence of the docuseries features many iconic cultural moments from the '70s and '80s. In telling this story, how important was it to contextualize it with the greater sociopolitical environment of this time period?

I'm a moviemaker, so I have so much love for the '60s, '70s, '80s movies. Maybe it's our European American dream. So, when we talked about this with the people at Netflix, I loved the idea because I felt that in the '70s especially, in the U.S., it was just after that very specific youth revolution, and many things changed. For me, Billy Milligan was at the turn, especially with the science at the time.

It was maybe the last big turn, and something very interesting. Cinematically, I loved the aesthetic of it, the cars, everything, for example, was much more interesting than today when you're traveling everywhere in the world, and very much of it looks the same. In the social aspects, I liked to focus on the cultural turning point of the U.S. in the '80s — there were many things that led me to that introduction.

Throughout the show, there's a lot of debate over whether Billy's condition was real, and connecting it with his violence. What were the internal conversations like about approaching issues of stigma and representing mental illness and personality disorders?

I was very attracted by psychiatry in ["Exit"] my first movie about a serial killer, so I've always been involved and very interested in that. In Europe, we have kind of another approach about psychiatry, and a different history. So when multiple personality [disorder] suddenly arrived, I heard about this about 20 years ago. After this, I was shocked and puzzled by Milligan. When I heard about Billy's story, the movie "Split" arrived, and I began to think about how there could be more room for a story like this to exist in the U.S. than in Europe.

I try to have a very specific approach and not just have the U.S. perspective, and be very open to European perspectives. I talked a lot to French psychiatrists, and they pushed me to dive a little more into this. I did a couple other documentaries, and just before I did a documentary on a conman known very well-known in France, Christophe Rocancourt, so I've always worked in that space of thinking how the mind is working, how gangsters worked, how common people would understand and react.

So, it's a wide field of research for me all the time, and it's very interesting because when you're making movies, you're creating worlds. When you're creating documentaries, you're just adding to the reality, trying to find anything to make it clearer. A movie is the opposite, where you're trying to escape reality. It's important to have that back-and-forth travel between reality and fiction movies. In documentaries I try to dive and dive and dive and go very far into the subject, like an obsession, and it's different with movies.

Billy is one of the least clear subjects I've worked on, where in France, they'll say it's very clear – not true. On the other side, in the U.S., people were believing in this. It was very interesting to be between, and try to understand why. The answer was, in France, we hadn't had cases like this. It's not because it doesn't exist, it's because the concept does not exist there. So for me, in this documentary, the thing was not to believe or not believe Billy Milligan, but to understand how his story happened in the '70s and '80s in the US, why the social context allowed this, explore the words of psychiatrists and lawyers. I hope the documentary opened that door to the viewers.

There's often criticism of true crime stories that focus on sexual assault perpetrators over their victims. What went into the decision to focus more on Billy than his victims?

In the beginning, I was focused on the victims, but the story became how Billy became a star in America. It was the beginning of this society of image, marketing, and so on, in the '80s — there wasn't room being made for the victims. [The documentary] was in the logic of what was going on in the '70s and '80s, the media's images were going faster and faster.

There was a lightning focus on Billy, where it was kind of a circus for the media. Then, the reality of what he had done disappeared because the circus was more interesting. This is why I fought against some people we interviewed, because they were still adding that, believing Billy. And I found that very strange, and wondered, "What about the victims?" I think that line came out three or four times in the documentary.

We found one victim, but she never answered, because what's very strange about true crime stories is to try and go back 40 years, where victims have tried to forget everything, to come back and reactivate the pain of what they experienced. So, we tried to have connections with them, but it was too hard because some forgot everything.

This is what created Billy Milligan, which was an incredible story, because having 10 and then 24 personalities — he was seen as a freak for a long time, for many people in the press, until the '90s, where even when he was known to have committed the crime, we were focusing on his story, not the victims. This is the world we're living in. I don't remember having a movie on victims of serial killers, but we have thousands of movies about serial killers. It may be that we're just following that kind of guy, or this modern way of how our society likes to be afraid from those kinds of people.

So to clarify, there was effort made to contact and include voices from Billy's victims or their loved ones?

Yes, and so for example, we tried to contact one's family, but found they didn't have living relatives anywhere, and it was 40 years ago. When we talk about this kind of story that happened the '70s and '80s, it's very hard to find living victims, because many will not want to testify or most of them, like the other people we interviewed, were quite old today. This is always the main problem, when you get too far from the story, where you don't have witnesses today. For sure, you want to have everything, you want to have all the perspective and all the reality. But as I said, there are problems with reactivating the pain of the victims, or where it's not really possible to catch them, because they're dead or too old.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

How would you respond to common criticisms that true crime projects like "Monsters Inside" tend to reduce victims to a footnote, while elevating violent men?

The strange thing about this miniseries is, it's not really just true crime. From the beginning, there is the mainstream media producing true crime stories, but our subject is much wider. Netflix hadn't done this sort of commentary before, where we start with this event, and try to find the reality of it. With Billy Milligan, we know he is guilty, and everyone says he was guilty of rape, but the problem is that he wasn't convicted for reason of insanity, then afterward, for the alleged murders, because there was no body. And you can't go to the end of a story in true crime unless you have those pieces of the story.

From the beginning, we knew we were going somewhere else. The issue was to try to tell a story and try to open doors for the audience to something different. This is what I try to do in all my documentaries, just to give people the choice to believe in this or question if Billy was a victim in some way or not. The whole thing is, after the four episodes, people have their own perspective about what they've seen and the story. In every documentary, you have that judgment at the end of is he guilty or not. But on this one, it's not the same thing at all.

Billy is notably white, and was able to evade consequences for some of the horrifying acts he's believed to have done. Were there internal conversations about addressing white privilege in the documentary?

Yes, for sure. So, it's in Ohio, which was quite interesting to get into that Midwest state and try to understand the logic of it in the '50s. I was surprised, shocked by the relationships with race in the '50s there. And certainly, if Billy Milligan were a Black man, he wouldn't [get away with] what he did as a white man.

Specifically because Ohio was this middle America state, when I arrived there, I was used to working in the east or west coasts — there, it's not the same U.S., the same people, the same logic. As a European, I was surprised. Being in Ohio was different. How Milligan escaped confinement, why people listened to him, why people believed him, those were examples of how he came from this [white] community. The mayor of Columbus was of course a Democrat, and he was against Billy, thinking Billy's case was a mistake and he was faking, and another leader was more believing and was a Republican. It's interesting that even in the '70s, there was that political fight, and conflicts between social classes and communities already in this country, in middle states.

Some lines from the interview subjects really stick with you — there's Billy's friend Jim Murray saying "people only knew Billy as a rapist" and how he wanted to "show another side to him" in Murray's play. In contrast there's a law enforcement agent who's upset that "no one cared about Billy's victims" because of the fixation on his mental illness. How did you balance these dueling perspectives throughout the series?

It was very hard, because Kathy [Milligan's sister] knew him more than anybody, and the first thing we talked about was more about how she couldn't accept he killed people despite knowing he did it, or that he raped girls. This is the first thing she told me. She didn't tell me he's not guilty, she always told me from the beginning, he is guilty, and he should have never done this. But it was her brother, and she was the only person on Earth who could protect him. That kind of duality of emotions was much more focused around her, Kathy.

From the beginning, I was skeptical of Billy's story, and I felt I knew he was lying from the beginning. That was what I felt deep inside. I had empathy for his victims from the beginning. But my job is like, in a trial, you need to show everything, you can't only be on one side or only show black and white. I knew what I felt and what I was thinking, but knew I needed to show and tell everything, including his traumas and his past with Chalmers [Milligan's allegedly abusive stepfather] and such, building the monsters he had inside. I needed to go very far and give all the things I knew of him. It's not really a duality of Jim and the man from the FBI, or that they're totally different, but it's that they didn't have the same approach. Even with Jim, when he talked about Billy, his friend, you could still hear Jim's his fear and know he also feared Billy.

The conclusion of Episode 4 is particularly haunting as you see how Billy becomes a literal celebrity, hanging out with celebrities and playing an active role in developing movies about him. The episode seems critical of this. Were you concerned this documentary series could unintentionally be part of the issue of celebrification of violent men?

To be more specific, I feel Billy became a star even before the documentary. Hollywood was a kind of major achievement for him, but I felt he already was a celebrity with the locals in the '80s. The fact that these books were made about him, that was already the project of making him somebody, a branded guy. The whole thing began much before ["Monsters Inside"]. Hollywood was the end of all this.

With the last part of the series, and they were writing his story in Hollywood, for sure he met big people, but I felt this was the end, because this was where the reality came. When [James] Cameron realized Billy had already given the rights to his story, everything was gone. It took about 40 years to have the rights back, and to make something on this story. So, Hollywood was much more the end of his story.

He was a celebrity, but when he was back in Miami and then later in life, there was more realization he was a conman, even though people were certainly fascinated by his story, and didn't care about the morality of it. This was the crazy thing, and especially as directors, you're meeting a lot of people, like criminals, gangsters, who want to be famous, and want to tell you their story. Most of the movies, except maybe comedies, are more like this, and how we try to understand and talk about human beings, and the way they may freak out, or screw up. So arriving in LA for Billy, it was that kind of freak movie for a lot of people. So I don't really think he was fully a celebrity, and he just met celebrities because he was kind of in this network — but they very quickly understood they couldn't do his movie and it quickly just exploded, and went back to reality.

"Monsters Inside: The 24 Faces of Billy Milligan" is now streaming on Netflix.

Shares